The Evidence for Active Recall and Spaced Repetition: What Research Actually Shows

Most people study by reading the same material over and over. It feels productive. The information seems familiar. And then, a few days later, most of it has vanished.

This is not a personal failing. It is a well documented feature of how human memory works. And it is exactly the problem that two of the most researched learning techniques are designed to solve: active recall and spaced repetition.

But rather than simply explaining what these methods are (we cover that in our complete guide to active recall and spaced repetition), this article looks at what the research actually shows. What studies have been done? How strong is the evidence? And what makes these approaches more effective than the alternatives?

The Forgetting Curve: Where It All Starts

In 1885, the German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus conducted the first systematic experiments on memory and forgetting. He memorised lists of nonsense syllables and then measured how quickly he forgot them over time.

What he found was striking. Memory does not fade gradually and evenly. Instead, most forgetting happens rapidly in the first hours and days after learning, then levels off. This pattern, now known as the forgetting curve, has been replicated consistently across more than a century of research.

The practical implication is important: if you learn something and do nothing with it, you will lose most of it within days. But if you revisit the material at carefully timed intervals, you can dramatically slow that forgetting. This is the foundation on which spaced repetition is built.

The Testing Effect: Retrieval Beats Rereading

One of the most significant findings in modern learning science is that testing yourself on material is far more effective than simply studying it again. Researchers call this the “testing effect.”

The landmark study was published in 2006 by Henry Roediger and Jeffrey Karpicke at Washington University. In their experiment, students read prose passages and then either restudied the material or took a recall test (writing down everything they could remember, without feedback). Five minutes later, the restudying group performed slightly better. But when tested two days and one week later, the group that had practised retrieval dramatically outperformed those who had restudied.

The numbers tell the story clearly. Students who only restudied the material forgot 56% of what they originally recalled within two days. Those who practised retrieval forgot just 13% over the same period (Roediger & Karpicke, 2006, Psychological Science).

This result was surprising, even to the students themselves. The restudying group reported feeling more confident about their ability to remember the material, despite performing worse on the delayed test. In other words, the strategy that felt most effective was actually the least effective for long term memory.

Retrieval Practice Outperforms Elaborative Studying

A natural objection is that perhaps more “active” study methods, such as creating concept maps or detailed summaries, would match or exceed retrieval practice. This was tested directly.

In 2011, Karpicke and Blunt published a study in Science comparing retrieval practice with elaborative concept mapping. Students read science texts and then either practised free recall or spent the same amount of time building detailed concept maps of the material (a technique widely used in education).

One week later, students who had practised retrieval recalled significantly more information. This advantage held even when the final test involved creating concept maps, the very skill the concept mapping group had practised. The researchers concluded that retrieval practice enhances learning through mechanisms specific to the act of retrieval itself, not simply through deeper processing of the material (Karpicke & Blunt, 2011, Science).

This finding matters because it challenges a common assumption in education: that the best way to learn is to engage more deeply with material during study. The evidence suggests that practising the act of remembering is more powerful than practising the act of studying.

The Large Scale Evidence: What Meta Analyses Show

Individual studies can be compelling, but the strongest evidence comes from meta analyses that pool results across many experiments.

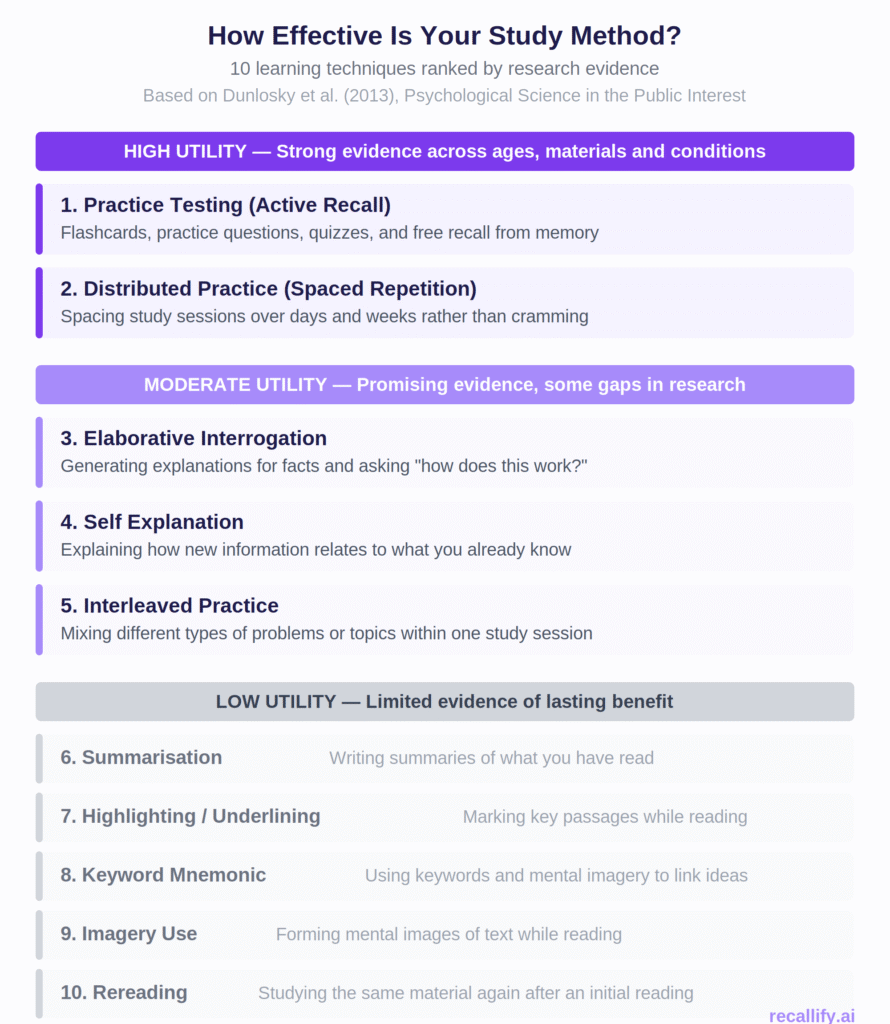

In 2013, Dunlosky and colleagues published what is arguably the most comprehensive review of learning techniques to date. They evaluated ten common strategies used by students and rated each one for effectiveness. Their findings, published in Psychological Science in the Public Interest, were clear:

Rated “high utility” (most effective):

- Practice testing (active recall)

- Distributed practice (spaced repetition)

Rated “low utility” (least effective):

- Highlighting and underlining

- Rereading

- Summarisation

The review drew on hundreds of studies and found that practice testing and distributed practice were effective across a wide range of ages, materials, and testing conditions (Dunlosky et al., 2013, Psychological Science in the Public Interest).

A subsequent meta analysis by Donoghue and Hattie (2021), building on Dunlosky’s framework with 242 studies and over 169,000 participants, confirmed these findings. Distributed practice and practice testing were again the most effective of all ten techniques examined.

The irony is that the methods rated lowest, highlighting, rereading, and summarising, are the ones most commonly used by students. The methods rated highest are used far less often.

The Spacing Effect: Timing Matters as Much as Method

Active recall works best when combined with spaced repetition, the practice of reviewing material at increasing intervals over time.

The spacing effect has been studied extensively. Cepeda and colleagues (2006) conducted a quantitative review of 254 studies involving over 14,000 observations and found a clear pattern: distributing practice over time consistently produced better retention than massing the same amount of practice into a single session (Cepeda et al., 2006, Psychological Bulletin).

The optimal spacing depends on how long you need to remember the material. For a test next week, reviewing after a day or two works well. For material you need to retain for months or years, longer gaps between reviews produce better results. This is the principle behind systems like the Leitner flashcard method and modern spaced repetition apps.

Beyond Students: Active Recall for Everyday Memory

Most research on active recall has focused on students and exam performance. But the underlying principle applies to anyone who needs to retain information: professionals keeping up with training, people managing health conditions, or anyone who simply wants to remember more of what they read and hear.

For people living with memory difficulties, whether from brain injury, neurological conditions, or everyday cognitive fatigue, the concept of retrieval practice can be adapted into daily habits. Recording a meeting and later trying to recall the key points before checking the summary. Reviewing notes from a medical appointment using a quiz rather than just rereading them. These are all forms of active recall applied to real life.

Dr Sarah Rudebeck, a Senior Clinical Neuropsychologist with a PhD in memory disorders from Oxford and co founder of Recallify, notes that active recall principles are already used in clinical rehabilitation settings: “The evidence for retrieval practice is robust, and it translates well beyond the classroom. For anyone supporting their memory, the key insight is simple: trying to remember something strengthens the memory trace far more than passively reviewing it.”

Recallify’s quiz generation feature applies this directly. When you upload notes, recordings, or documents, the app automatically generates quizzes based on the content, giving you structured retrieval practice without needing to create flashcards manually.

What the Evidence Does Not Show

It is worth being honest about the limits of the research:

- Active recall is not a cure for memory disorders. It can support learning and retention, but it does not reverse neurological damage or replace clinical treatment.

- Not all material benefits equally. Active recall is most consistently effective for factual and conceptual knowledge. Its benefits for procedural skills (like playing an instrument) are less clear.

- Implementation matters. The research shows the technique works, but putting it into practice consistently is the harder challenge. Spacing schedules, self testing habits, and finding the right tools all affect real world outcomes.

- Most studies use young, healthy university students. While the principles are well established, more research is needed on how active recall works for people with cognitive impairments, older adults, and neurodiverse learners.

Practical Takeaways

If you want to apply the evidence to your own learning or memory support:

- Test yourself rather than rereading. After studying material, close the book and try to recall what you learned. This single change has more evidence behind it than almost any other study technique.

- Space your reviews out over time. Do not cram everything into one session. Review after a day, then after a few days, then after a week. The gaps between reviews are where the real strengthening happens.

- Do not trust how it feels. Rereading feels easier and more productive. Retrieval practice feels harder and less certain. The research consistently shows that the harder strategy produces better results.

- Use tools that build retrieval in. Whether it is physical flashcards, a spaced repetition app, or a system like Recallify that generates quizzes from your own content, the goal is to make retrieval practice a regular part of how you interact with information. You can get started here.

- Start small. You do not need to overhaul your entire approach to learning. Even adding one recall session per week can make a meaningful difference over time.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the strongest evidence for active recall?

The most cited evidence comes from Roediger and Karpicke’s 2006 study, which showed that students who practised retrieval retained significantly more information after one week than those who restudied the same material. Dunlosky et al.’s 2013 review of ten learning techniques rated practice testing as one of only two “high utility” strategies, alongside spaced repetition.

Is active recall better than making notes or mind maps?

Research suggests it is, for retention purposes. Karpicke and Blunt (2011) found that retrieval practice produced better learning outcomes than elaborative concept mapping, even when the final test required students to create concept maps. Note taking and mind mapping may support understanding during study, but adding retrieval practice afterwards improves how much you remember long term.

Does spaced repetition work for all types of learning?

Spaced repetition has been shown to work across a broad range of material, ages, and contexts. It is most consistently effective for factual and conceptual knowledge. The optimal spacing intervals depend on how long you need to retain the information. For material you need to remember for weeks or months, longer gaps between review sessions tend to produce better results.

Can active recall help people with memory difficulties?

The underlying principle, that practising retrieval strengthens memory, applies broadly. However, most research has been conducted with healthy university students. For people living with brain injury, neurological conditions, or cognitive impairments, active recall can be a useful strategy alongside other forms of support, but it should complement rather than replace professional guidance. Tools like Recallify are designed to make retrieval practice accessible for people who find traditional study methods overwhelming.

How often should I review material using spaced repetition?

There is no single “correct” schedule. Research by Cepeda et al. (2006) found that the ideal spacing depends on how long you need to retain the information. A general starting point: review after one day, then after three days, then after one week, then after two weeks. Many apps automate this process based on how well you recall each item.

Is highlighting an effective study technique?

According to Dunlosky et al.’s 2013 review, highlighting and underlining were rated “low utility” as learning strategies. While they may help you identify key information during reading, they do not promote the kind of deep processing that supports long term retention. Combining highlighting with active recall (reading, highlighting, then testing yourself from memory) is a more effective approach.